An Afternoon with Francesca Vaira of G.D. Vajra

Francesca poured her family’s wines and shared the vision and philosophy that animate the work

Francesca Vaira fetched me from my hotel in Alba, her infant son, Giuseppe, asleep in the back seat. It was a Sunday afternoon in early February, the sun brilliant after a sodden week that I’d spent in tasting rooms and lecture halls. Sunday is family day in Italy, but Francesca made the time. First she toured me around the Barolo hills, rising into the medieval town itself and stopping next to vineyards to survey the scene: vines upon vines.

After arriving at the G.D. Vajra winery in Vergne, halfway between Barolo and La Morra, we briefly toured the production room. It was cathedral-like, the light spilling through the bespoke stained-glass windows designed by Padre Constantino Ruggeri. Then we sat for a tasting.

Francesca’s father, Aldo Vaira, had taken over his family’s estate in 1968. His father, Giuseppe Domenico Vaira (G.D.), gave his name to the effort. That support hadn’t always been assured. When Aldo was a teenager, his grandmother spotted him marching at a political protest. His father, the son of a military man who’d fought the fascists, was furious. He banished Aldo to the countryside to live with his grandparents. It was supposed to be a form of punishment. It backfired spectacularly.

That summer, Aldo fell in love with agriculture, and on his return home announced he would become a farmer. More outrage. Giuseppe, originally from Torino, had always assumed his son would adopt a more cosmopolitan profession. Okay, okay, he relented at last. But you must also attend university.

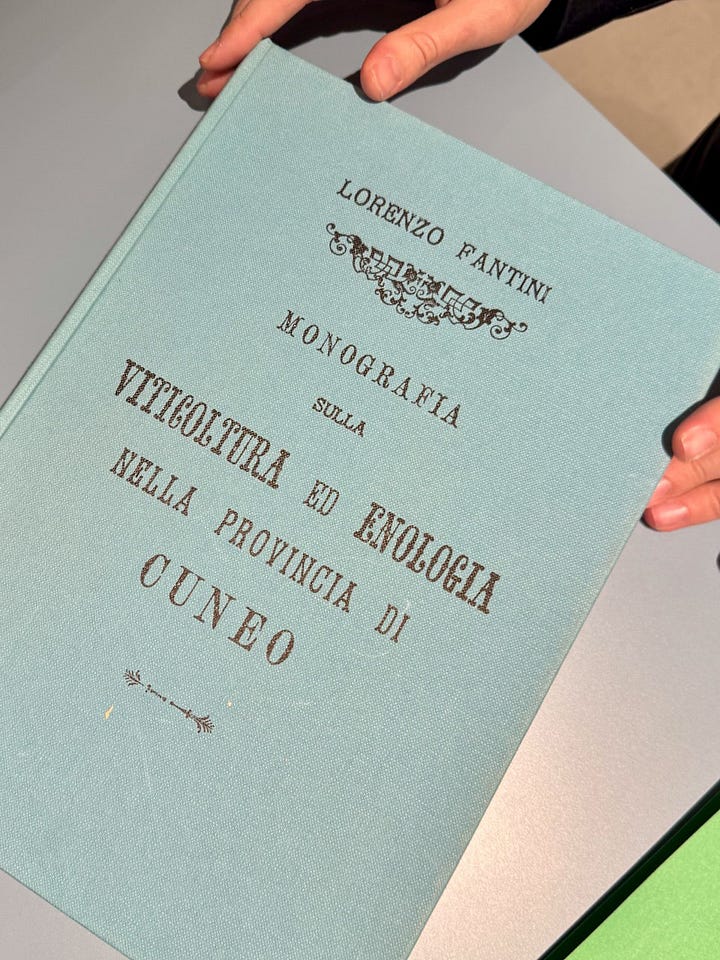

So Aldo went off to Torino to study winemaking. He swiftly discovered the philosophies of the academy ran counter his back-to-the-land ethos. The curriculum was mainstream, modernist, heavily funded by agrochemical companies. Fortunately he found a supportive professor, Francesco Garofalo, who would gather a group of like-minded students, close the door, and lead deep discussions about ecologia, sustainable farming, and perpetuating the knowhow of the past.

Returning to the winery, he committed to organic production, earning certification in 1971, a first in the region. He also championed native grapes Nebbiolo, Freisa, Dolcetto, and Barbera (while cultivating a plot of Rhine Riesling as a pet project).

Today, Aldo, his wife, Milena, and their children, Giuseppe, Francesca, and Isidoro, own and manage 80 hectares in the Langhe, producing wines at their main facility and their newer estate in Serralunga. Giuseppe makes the wine, Isidoro helps with viticulture, and Francesca works with her mother in hospitality and communications, responsible for vision and philosophy.

Over nearly two hours we had a rangy discussion while her son slept alongside us. Midway through the tasting, Aldo and Milena arrived from their overnight flight from New York and sat down with another couple who’d stopped into the winery. “Family Sunday” means something else when your family makes wine.

The interview has been edited and condensed for clarity. My tasting notes follow the interview.

Meg Maker: Tell me about Vajra’s farming philosophy.

Francesca Vaira: My dad learned winemaking in the late 60s, early 70s. The university had sponsors from agribusiness, and while he did learn about organics and biodynamics, that was more like a special thing. In the official classes, the teachers invited the sponsors to come talk about the market and top issues. One day, they suggested putting — not concrete, but the same thing you put on the street —?

MM: Gravel? Cobbles—?

FV: Like the black [blacktop]? — between one row and the other. Can you imagine, Meg? They were like, “It’s perfect! You do it once in your life, then you don’t have to be worried about the rain, the grasses growing, cutting grass. You don’t have those grasses scratching your ankles while working. Sounds perfect!” It was one of those dramatic moments where you say, Okay, you could be a Yes Man, but this isn’t really what you’re being asked to do. You’re being asked to work with your mind.

My mom has a beautiful way to express our way of working. She says, here at Vajra, we work with science and consciousness. In Italian: scienza e coscienza. The root is about knowledge itself. You know the science — the scienza, technical things — and coscienza says you judge with your heart. It’s about knowing chemistry and knowing, as much as you can, how things work. And then judging if it’s working.

MM: The 2024 vintage was especially wet. What was the hardest part of using organics last year?

FV: It was really wet, and on a type of soil that’s mainly clay, so the effect is like water and soap. It makes it extremely dangerous to work. Many people gave up on organics. Considering it takes at least three if not four years to turn everything organic, giving up on farming that way was a big decision.

When Vajra started, late 60s and early 70s, there were some not easy vintages, at all. But we pushed always to source vineyards with the best exposure and microclimates for sun and ventilation, or the capability of a certain vineyard to get drier faster than others.

Going through a bunch of tough vintages in recent times, I’m thinking 2014 and 2018, taught us that if you gave up in the middle of the season — just because some journalists said it’s going to be tough and nothing good will come of it — you wouldn’t be able to recover. Nebbiolo is a kind of grape that makes you fight until the end, and then it gives you almost like a caress, like a reward for all the effort you put into farming.

So never give up. You have to believe something magic, something good is coming. Maybe the season’s extremely dry, and you do a lot of work in the fields to have the healthy vines and fruit, then maybe you have a rain before the harvest that’s rebalancing and everything turns for the best.

It’s a lot of physical work. But the tougher the vintage is, the more people love their job, and the more energy, the more effort, the more money they will put to it. If you work looking at your balance sheet you will spend less money. But there’s an old story of a farmer who was afraid of the bad season and put less and less seed in the ground. What is this going to bring?

MM: Less and less product.

FV: He starves. So as farmers, we need to have huge faith in what’s coming next. Sorry, that was a very long answer!

MM: It’s perfect, because it speaks about determination and hard work. [Shifting to the tasting and the first wine, Albe.] Albe is a fanciful name?

FV: Yes, the fancy name. Albe is the plural of alba, so “multiple sunrises.”

MM: The word for sunrise is “alba?” I did not know that!

FV: Yes! So, why multiple sunrises? Because of the three vineyards where we farm Nebbiolo [Bricco delle Viole, Fossati, and La Volta]. When we blend those together, it gives birth to Albe.

MM: Do you position it as an entry-level Barolo?

FV: “Entry level” is an interesting concept, but dangerous at the same time, because most people expect it’s not high quality. If your first step into our world is not a good step, you won’t walk further, right? If the first wine your husband had shared with you wasn’t a good wine, you wouldn’t be here.

MM: I probably wouldn’t be with my husband, either.

FV: That’s a fair answer! When you discover something you’ve fallen in love with, you want other people to be able to fall in love with it too.

I went to high school in Alba. Classmates asked me, “Is your father winemaker?” Yes, I said. “Does he make Barolo?” Yes. “What does Barolo taste like?” That was a moment I realized I’d spent a lifetime sharing wine with older people who knew more than I knew, and I’d never had to tell them how the wine tasted.

MM: What did you say to your classmates? How did you respond?

FV: I realized that, in terms of language, I had to start from experiences they’d already had. The thing that they were drinking that had the most tannins — do you know what it was?

MM: Black tea?

FV: There’s a Ferrero factory based in Alba that makes an iced tea — which of course has tons of sugar as well — but that was their reference for tannins. And when they would go out, what would they drink? A Caipirinha, Caipiroska — can you imagine? Just sugar and alcohol.

My friends were curious, very smart, and they would either steal a bottle of wine from their parents’ cellars or go to a grocery store to buy their very first Barolo. The kind of Barolo you could get in 2000 had tannins from the stems, from traditional winemaking, and oak from the barriques, from modern winemaking. Nebbiolo is not easy, but those were gross tannins. I told myself, my friends are going to think Barolo is gross!

So that’s why “entry level” is a difficult concept, because the very first step into that world has to be dramatically good.

MM: I love that you were called upon at a young age to describe a complicated product, which even I struggle with after many years.

FV: This is one of the things I love the most about our job. When people come here to visit, it’s about understanding their backgrounds, because you cannot expect them to talk your way. You’re the one who knows the wine, so you have to talk their way and make it easy to understand.

[Moving to the Langhe Nebbiolo.] The grapes in the Langhe Nebbiolo are from the younger vines, around 10 to 20 years old. You can use them to make Barolo, but you will need to body-build. Instead, we like the fact that it already has its own structure, very bright aromatics, extremely long in the mouth. So it does not need to be forced.

MM: It’s priced less than the Albe?

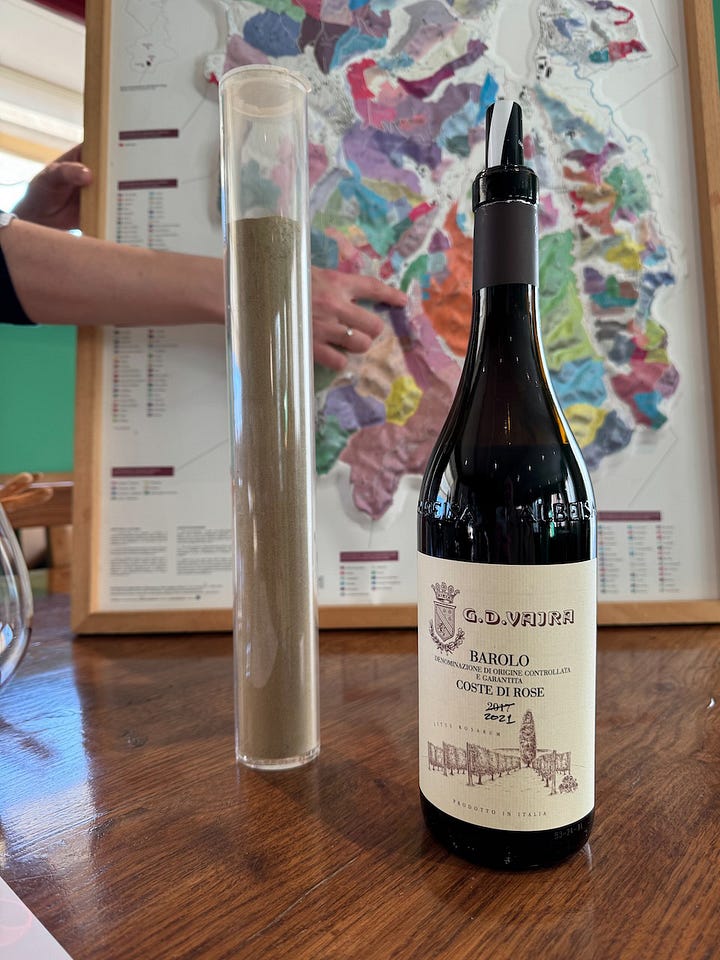

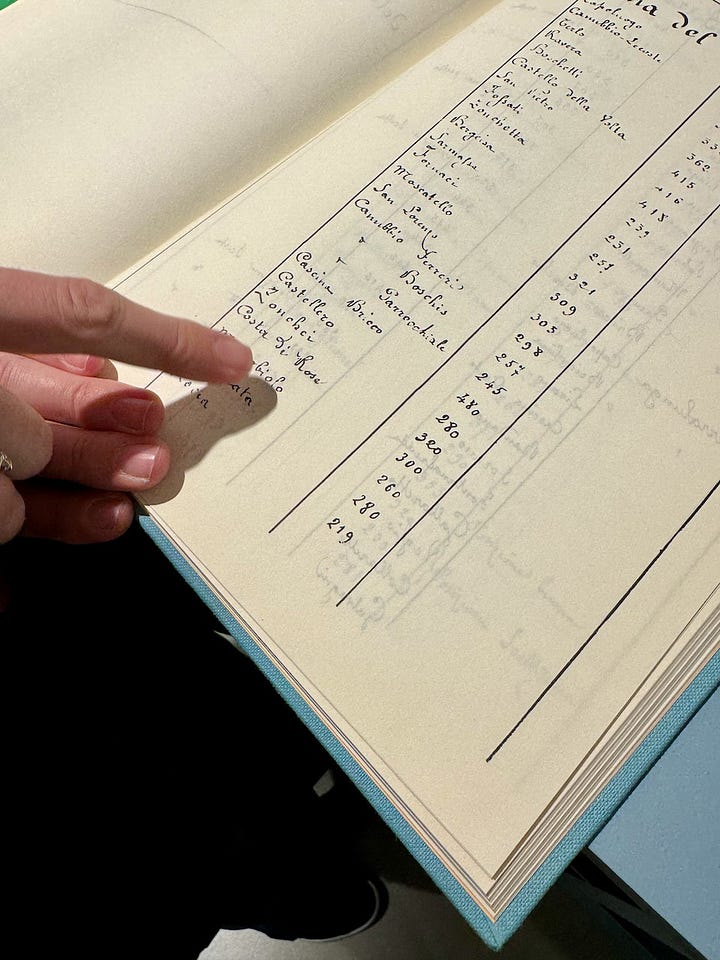

FV: Yes, Albe in Italy is €36 and Langhe Nebbiolo is €18. [Moving to the Coste di Rose.] The Coste di Rose vineyard has a crazy high concentration of sand, over 90%, which is extremely rare. That makes it leaner, more vertical.

You mentioned something curious earlier [in the car], about a different way of tasting wine. I hadn’t previously heard about geosensorial tasting, but I realize I’ve already been doing it. I think it applies to Nebbiolo beautifully, because Nebbiolo has the capability to really let the sense of place to talk. The way the tannins are cut in your mouth, the different volume the wine gets, it’s correlated with the soil.

MM: The Viole has lots of filigree, and the Ravera has beautiful harmony and length. One of the things that shows up a lot of my tasting notes is black tea. If it’s over-steeped it can be astringent, but if it’s perfect it lifts everything off your palate. It’s bright. It brightens you. These wines are all so young, right? What kind of runway do they have?

FV: I grew up hearing old folks saying about Barolo, “Oh, you have to wait twenty, thirty years.” I was curious that if something wasn’t tasting right in the moment, would that really change? Certain qualities of tannins do improve through the time, but if you have a green tannin, you can wait 100 years and probably it’s going to stay green.

With Barolo, you’re going have usually two or three years of a beautiful explosion of aromatics, but still the more astringent kind of tannins. Then Barolo tends to shut down. Ten years after the harvest is usually, to me, the best moment to understand Barolo; that’s where the nose and mouth open up again and you have, again, those floral aromatics, but the tannin structure is way more relaxed. Then you’re going to have, let’s say, another five, seven years when they stay more on the fruity and floral notes. Then, twenty years from the harvest, that’s when you start to add leather, tea, tobacco.

MM: I’d love to hear your approach to tasting. How do you evaluate or understand the wine? What is your process?

FV: I don’t know if I’m even able to answer.

MM: Also in English! So sorry.

FV: It’s just how I’m constituted, just within my nature. I don’t even know if this is what you’re expecting as an answer, but I’m curious about aromatics, and the fact that through the nose you can already start to create the feeling in your mouth, and next, validating it with your mouth. But at the same time, what I’m smelling doesn’t have to taste the same way. I also love a surprise.

MM: Sometimes it really does surprise you.

FV: When I was a child, my dad talked about the “digestibility” of the wines. It always drove me crazy, because it’s like, Come on, wine is meant to be a drink, you know? Then I realized some wines are so manipulated they’re lacking digestibility. A good wine, to me, is one that’s bright, with aromatics, it’s juicy, it keeps changing. But it’s also something you can drink and feel good.

MM: I’ve seen some mentions of that term, digestibility, but it’s not really used much in the English language wine literature.

FV: Yeah, that’s why I’m trying hard to translate.

MM: Well, it’s exactly that word I’ve seen, albeit not often. It’s when the wine feels like something your body can take in instead of having to deal with. Can you name some wines you really admire?

FV: This is extremely hard, because I’m open-minded. Riesling was my first love. I love acidity, I love freshness, and when I was young it wasn’t about tannin. Then when I grew up, I realized wine is something so magical that if you drink with an open mind, open heart, it can make you fall in love with this job. You can’t live this life with a closed mindset. You sip everything, you taste everything. Then you decide a careful way what you want to drink.

MM: Yes, because there are physical limits.

FV: Now people are using better judgment with alcohol. To drink has to be an enjoyment. It’s about learning how to enjoy the good things. Good food and wine can elevate each other.

FV: So we’re going to taste another trio. [Moving on to the Baudana wines.] Ever since Dad was young, he wanted to farm a piece of land in Serralunga. Then in 2008, just at the beginning of the financial crisis, he met with a colleague, and that night at dinner my dad says, “This guy from Serralunga, Luigi Baudana, is farming a cru called Baudana. He has no kids, and he’s looking for somebody to give continuity to the community.” I looked at my brothers and we looked at each other and all of us were thinking exactly the same thing. Like, okay, this is Dad’s big dream.

But Guiseppe said, “Dad, we need to be careful, because if in order to achieve this little dream of ours, we’re destroying a company, and we’re going make 20 people lose their job, it’s going to be a big No.” It was a big Yes to the dream and the opportunity, but a big No to being reckless. We spent a lot of time doing the pros and cons.

The day the contract was signed, Luigi brought tons of keys. He’d had a previous life as blacksmith, so he’d made three locks for every door on the property! My Dad said, No, no, I just need one key for each lock; you feel free to keep the other keys. Luigi and his wife, Fiorina, are still living above the cellar.

MM: I think it’s generous to put his name so much bigger on the label than your own company name, and without your crest or any of your other signifiers.

FV: It’s crazy. But the very first year we put on the market, we got the [Gambero Rosso] Tre Bicchieri, which was the award Luigi was trying to get his entire life, the award he always wanted. And we thought, Thank you for trusting us. Thank you for letting us try.

FV: Can we think about showing these two, the Barbera and Freisa? Normally I’d love to share the Dolcetto with you, but we lost so much of the production that we couldn’t make enough.

MM: Do you recommend tasting the Barbera first before the Freisa?

FV: Yes, probably. In the Freisa there’s such a huge concentration of tannin. Those two wines are, to me, the closest to Barolo. Especially Barbera. There is an expression about Barbera from Alba — some of the older folks say Barbera che è baroleggia [Barbera that is Barolo-like]. In a blind wine tasting, or maybe in a restaurant at dinner, unless you can focus on the density of the wine itself, it can be easy to mistake it for a Barolo.

MM: The color, though, is a giveaway, at least in a young wine. The depth of color, the opacity. Wow, this has beautiful acidity, so refreshing. The armature is acid rather than tannin. I’m sort of wandering around in the acidity now.

FV: That’s why I think Barbera is the easiest way to introduce people to the Langhe. Those flavors are already somehow like Barolo but way softer, more like more a New World style.

MM: We usually have Barbera in our cellar at home. Many of our friends don’t know about it, but it’s a beautiful wine and goes with so many foods. It’s affordable, delicious.

MM: [Moving on to the Freisa.] Aromatically it’s almost dried flower, dried rose petal, potpourri.

FV: The nose is interesting on Freisa. The name is also interesting. Our great grandfather used to call it fresia. It sounds like the French word fraise, strawberry, but actually fresia is freesia, the flower. So it is like potpourri. Also it’s a bit herbaceous, to me. Fruity, strawberry, floral, but also that herbaceousness.

MM: It’s almost like it promises you something soft and then goes KSSSH! at the end.

FV: That’s why this wine is called Kye — like chi è? you know, Who is it?

MM: This was a fantastic tasting. I appreciate your time, wisdom, insights, and hospitality.

FV: Would you like a coffee? I just need a few minutes with Giuseppe.

MM: No, I’m good! Thank you. I’ll just make a few notes and take some pictures, if I may.

FV: Absolutely. [Hoisting Giuseppe onto her lap.] Sorry for the socks of my son.

TASTING NOTES

2021 G.D. Vajra Albe Barolo DOCG

Floral, violets, purple flowers, crunchy fresh air. Juicy acidity and velvety tannins. Lovely rosy cranberry fruit.

2023 G.D. Vajra Nebbiolo Langhe DOC

Rosy fruit and flowers. Friendly fruit-forward, strawberries. Lively acidity. Distinctive Nebbiolo profile with soft fruit and accessible tannins.

2021 G.D. Vajra Coste di Rose Barolo DOCG

A sensation of dried fruits, violets, and herbs. It feels stony, with a drying flare at the finish. Bright, direct, and linear.

2021 G.D. Vajra Ravera Barolo DOCG

Ravera has layered soil with laminated marls. Aromas of dark red fruit, pomegranate. Spreading, dark, and chewy with balanced tea-like tannins. Texturally like corduroy. Long, integrated, beautiful.

2021 G.D. Vajra Bricco delle Viole Barolo DOCG

Called the “hill of violets” because the site warms early in the year and sports the first spring violets. Much darker wine, with dark red and blue and black fruit, black plum, blackberry. A rounded, substantial wine, mouth-coating and flavorful.

2021 Luigi Baudana Serralunga Barolo DOCG

This is a wine from three different sites in Baudana, Ceretta, and Costa Bella. Clear, bright, direct, linear; texturally the most austere of the three but delivering a juicy sluice at the finish.

2021 Luigi Baudana Baudana Barolo DOCG

Aromas of dried cranberry, dried strawberry. Tannins well integrated, velour rather than velvet. Sharp red fruit plays through.

2021 Luigi Baudana Cerretta Barolo DOCG

Cherry, rhubarb, dried cranberry aromas. Pleasant, beautifully integrated tannins with polished edges. Blazing red cherry at the end.

2022 G.D. Vajra Barbera d’Alba Superiore DOCG

Deep Purple color, opaque. Fruity and floral, with wildflowers and apple blossom, raspberry and raspberry blossom. Firm acidity.

2022 G.D. Vajra Freisa Kyè Langhe DOC

Dark flowers, dried flowers, potpourri, something darker, almost tar. Powerful tannins, really structured, with acidity that flies in at the end. Beautiful length.

I’m grateful to Francesca Vaira for her time, insight, and hospitality, and to Studio Cru for helping to arrange the visit. All wines were samples for review.

More interesting discussion about language!

Also, I really like that photo of Aldo through the lattice.