London, Backward and Forward

Revisiting London with pen in hand

I just returned from the UK, a work trip consisting of a short stint in London for an event and four days in Oxford for a conference. I’d lived in London during college, working on a student visa and sharing a basement flat in Pimlico. Last week, before my professional obligations began, I had some time to stroll around and reflect. Here’s my diary from that day.

The Brunswick Center, Camden, morning

Breakfast at a café, chicken and leek turnover, cappuccino. It’s 10:00 a.m. and my room at the hotel around the corner won’t be ready for three hours. So I wait and I write. My time until tomorrow’s lunch is unscheduled. Except for sleep.

I’m back in London solo this time. It feels like I was just here, riding the Piccadilly line from Heathrow into Zone 1, so familiar even seven months since last time. Forty years since the time before that.

Time accordions into itself, collapsing into its own gravity, pulling us all along.

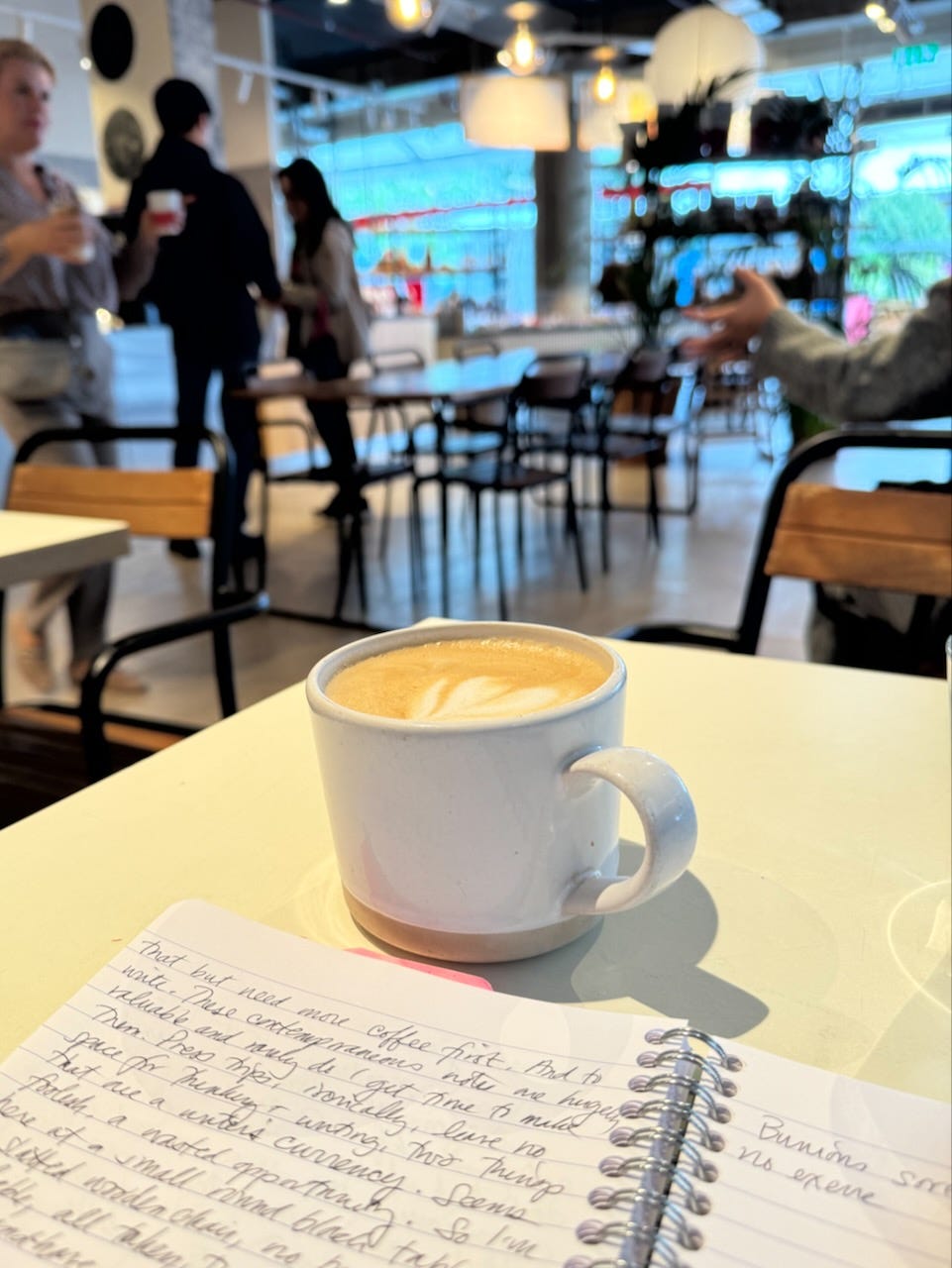

The British Museum is right around the corner. I may go but need more coffee. I need to write. Contemporaneous notes are inestimably valuable but I rarely get the time to make them. Press trips especially (ironically) leave no space for thinking and writing, two things that are a writer’s currency.

I’m seated at a small black table on a slatted wooden chair. No padded chairs available, all taken, the café version of haves and have-nots. Some people are working, some tending smiling children. There are a few attractive young professionals, urbane and relaxed even on Monday morning. I slept perhaps one hour on the plane, so would not call myself relaxed. I’ve never been urbane.

I just ordered a second coffee and switched to a padded chair, still warm. My feet are swollen and sore, ankles puffy from the plane. Cramped, no exercise, just the huff from dragging my case and carcass through airport to underground.

At Heathrow a family got onto the Piccadilly car with me and sat opposite, crowding knees against luggage, trying to make themselves small. Americans; a bag tag said home was Nebraska. Mom and dad in their 40s, two sons, maybe 15 and 11. Mom with wavy red hair, not graying yet, tired face. Overnight flight and weight of world. Dad, tall, mysteriously unfatigued. Three big checked bags, one with a Disney World tag, all with tattered ribbons that make them easier to claim on a baggage wheel, ribbons that reveal the family travels sometimes, not just this once. The older boy’s a redhead with freckles and a sweet, pure face, green eyes like his mom. The younger boy, hair almost red, with glasses that make him look older, erudite, striped white and black with red accents. I think he doesn’t enjoy being younger. Both boys seem fresh and sweet and smart. Dad dad-like, staring at his phone, mom closing her eyes, weary, boys with wide faces watching the suburbs of London slide by. I looked at her and him and him and him and thought, that could have been me, been us, in another reality, another dimension, a different life. We could have had two sweet, smart, red-haired boys that we took places, taught things to, showed things to, talked to, raised. I got misty looking into this mirror seeing myself and my husband and the two sweet humans we did not have, did not give birth to and love.

The British Museum is booked all day and also tomorrow morning. Of course. So I must meander the streets, stupefied, before rest.

Neal’s Yard, Seven Dials, late afternoon

I used to eat a hotpot here on my 30-minute break from the Natural Shoe Store around the corner. The yard’s different now, bougie, little metal tables outside the natural wine bar where I was lucky to get a seat on Monday afternoon at 5 p.m. I ordered a glass of Crozes Hermitage Blanc and it’s now arrived, golden-hued, smelling like lemon and oak and salt. It’s the perfect temperature, cool-not-cold, silken, satiny, expansive, expanding. A wine that shakes out its hair, brushes it in the sunlight while I watch.

When I was here as a 20-year-old, I knew nothing about wine. Nothing about anything.

The clouds break sometimes and there is sun against the orange and teal and yellow and brick. I’m in a beam now, sunlight raking the glazing, light reflecting onto me, prismatic. I wonder what Nicholas Saunders would think of this thing he wrought. Sitting here, writing at this outside table, I am both participant and part of the scenery, as people stroll through to gaze around, smiling as they discover the fairy charms of this triangular courtyard, as they aim and pose and snap pictures and peer at the screen and re-aim and re-snap for a better angle, better light. To see themselves in a better light.

Steve and I were here last Christmas. In the center of the yard was a big fir tree dressed in lights, plus bigger bulbs strung around the yard like a circus tent, guy wires tying the strings to a ring in the center. All of that, sans tree, is still up, apparently a permanent fixture. The tent-like armature of lights a big funnel to let out ideas, to let in stars.

Around me are readers of books, people on phones, pairs at two-tops trying to impress with veiled boasting. A young woman has just arrived, alone, and pulled out a notebook and pen. One of the sisterhood of writers. She looks 19 or 20, my age when I was first here, dressed all in black, slouchy sweatshirt over strappy top, shagged hair, kind of tousled. It’s a good look, sexy, the sweatshirt off one shoulder, Flashdance style, fully in style when I was first here.

The tables are emptying now. It comes in waves, it goes in waves.

It’s strange to be an adult here, all the years between then and now collapsing back into themselves. It’s different, I’m different, but place persists. In cities place is made by people, and a thread, maybe more like a rope, binds place together across decades. The fruit and veg stand in the yard has transformed into a café. The cheese shop is now the natural wine bar. The bakery is now something I can’t read from here. The pigeons are the pigeons, not the same pigeons but the same ur-pigeons. The Whole Food Warehouse is gone. That was the anchor, the original draw. People shop at Sainsbury’s now, or Waitrose, putting packaged whole foods into their trollies along with frozen meat pies and pre-made salads and cheddar biscuits and Fairy washing-up liquid. All the essentials in one store, no need to traipse across London to buy oats from a dusty bin in Neal’s Yard.

I’ve almost finished the Crozes. It got warmer as it sat, hotter, too. Some of its golden ephemera has spirited into the breezy atmosphere, up the circus tent. Maybe the pigeons can smell it.

Tomorrow I’ll visit Warwick Way.

Lamb’s Conduit, Bloomsbury, evening

I reserved the dining room but decided on the bar. I didn’t want the full menu, too much. The bar is brighter and I can see through to the active street, light raking in. I’ll order Lambrusco and snacks. No langoustines on the menu despite early warning. The server was kind and helpful, suggesting a mix of plates to make a meal.

My feet hurt. I walked miles.

The Lambrusco is perfect, amber ruby and frizzante, lots of acetic. Not aromatic but faintly saline and stony.

Near me a table of six young diners is speaking a mix of English and a language I don’t recognize. No one is older than 30, five men and one woman. There’s serious Bordeaux on the table, I think Haut Brion, and a chilled but unopened bottle of Sauternes. It’s chilled because it’s sweating.

I now have an embarrassing array of foods before me.

Two older men just sat at the corner window table, a Brit and an American. Business associates.

I have never been here in the summer, when London effloresces into café, pub, and street culture. Some indoor galleries make this possible year-round, or in the rainy heat, but there’s no substitute for being in the middle of street business. LOOK RIGHT! I don’t associate café culture with Britain, that’s another difference from the ’80s, or perhaps it’s just because when I lived here in the ’80s it was winter, a long bone chill from September to March. The street was for swift commutes from flat to underground, underground to work, all unwound on the way back home. On fair days I might linger awhile, perched in the Yard or huddled in a doorway eating steaming chips from a paper cone, black collar turned against the cold.

Thatcher’s London was a grizzled metallic gray dusted with soot and sadness.

The young Bordeaux lovers have vacated, taking their Sauternes with them. Two staff have come to clear the table. I eyed them and smiled. Haut Brion? I asked.

Yes, one said. Serious stuff, a ’79.

What’s the corkage? I asked.

They didn’t bring it, said the second. It was on the list. It was on the list. We had only one bottle.

There is some left, said the first. I wouldn’t have left it.

So now the staff can have a taste, I said.

She smiled, hoisting the bottle and clinking remains, two ounces in a single glass, into her crowded arms.

I worked hospitality here too, catering, before the stint at the Natural Shoe Store. The contrast between my status and those I served was a gulf unnavigable. My life now is a surprise turnaround. Thatcher’s London permitted no optimism. As a young woman I expected nothing for my future, although my colleagues eyed me with resentment: American, university student, blessed with the promise of upward mobility. But I was poor and cynical and could not fathom a future in which I would be able to finance the comforts of a plate of mortadella with cornichons and a glass of Lambrusco in a natural wine bar in London on a Monday night after an overnight flight in Economy Comfort that I’d paid for myself. To say nothing of the fact that I was in town to attend a luncheon at an elite social club for a global organization of wine writers, of which I was chair, after which I would take a train to Oxford University for an academic symposium at which I would deliver a paper about the languages of Pinot Noir. I would have considered all of these propositions absurd, had you even been able to explain them in terms I could understand. The academic piece might have seemed less preposterous, because I was a fervent and dutiful student. But the wine? Back then my expertise extended to Hearty Burgundy, and not even much of that.

Now I have a Dolcetto d’Alba for the last of my mortadella. I sense flowers, maybe violets, black raspberries, and earth. Texturally it’s silky with vanishing tannins, just smooth fruits and that purple flowery note. The finish feels black.

I suspect the most unimaginable part of my future scenario would have been the fact that I could afford any of this experience at all. I didn’t grow up knowing how money worked. I had a bank account and understood compound interest, but money was a thing managed on slips of paper that got tucked into a corner of the kitchen counter behind my mother’s purse, a project to be undertaken once per month to keep creditors quiet. I babysat as a teen, then worked at an art store for something like $1.50 per hour, netting a few hundred dollars per summer. When I majored in art my father told me, Get a skill. But how to get a skill? I was not raised to get a skill, nor to deliver one. I was raised to think and talk. So here I am, thinking and talking. Meaning writing. And also here I am, ordering confidently from a by-the-glass list at a great by-the-glass place, starting with Lambrusco and mortadella going to Dolcetto, because Northern Italy.

Small pours. Maybe I’ll end with Champagne.

There’s another solo diner here, reading a book, the quiet counterpoint to the person at my own table furiously scribbling notes. Notes for my memoir. Notes about my memoir. So, what is this memoir? Does it talk back and forth across time, as I’m doing now?

The soundtrack back then was Steely Dan and the soundtrack tonight is Steely Dan. Peg, Josie; Aja, the whole album.

Events accordion. Time is more than elastic, it is simultaneous. I am 20 and standing in the cold and Neal’s Yard eating a Cox’s Orange Pippin as the greengrocer smiles at my revelation that the top tastes different from the middle and bottom and the outside tastes different from the inside. I am 59 and sitting in Neal’s Yard drinking a white Crozes Hermitage and actually knowing what that means. Drink Crozes in 1986 and Crozes in 2025 and it’ll be different but the same. Like the pigeons: different but the same. Like me: different but the same.

I have ordered a finishing splurge of Pierre Peter’s Brut Blanc de Blanc Cuvée Reserve. The server was delighted and intrigued, helped me choose the sparkling that was most recently opened. Freshest. Now I’m texting Steve, wishing he were here. This evening would have been so different with him. I’m used to dining alone, or alone with strangers I’m traveling with, meaning alone. I like to write when I’m alone-alone because it says I’m not alone; I’m with myself.

I’ll go to Warwick Way tomorrow. It feels important to see the house with the basement flat with the rats and damp, with the flat with no kitchen, just hotplate and dorm fridge and no sink except in the bathroom. I lived there with two other American women, recent graduates, me a junior. I know no one there now, the landlords long gone. So I’ll stroll the neighborhood, even in this heat, retracing the path I used to follow to Victoria Station to commute first to Harrod’s, later to the catering kitchen in South London, finally to Neal Street.

The champagne is taking forever.

A group of American women has filtered piecemeal into the bar, friends, seated all together now. They are finishing graduate school and talking animatedly about the jobs they’re starting, weddings they’re attending, travel they’re planning. I heard Tanzania, or was it Tasmania? Their jobs at multinational companies and where they will be based and their pay rates and myriad early career preoccupations. They are not like the girl I was when I lived here. They’re a few years older but mostly they’re not like that girl because they are cosmopolitan and also chatty about their cosmopolitanism.

The champagne never came. I asked for the check.

The couple at the next table noticed. We were wondering when they were going to bring your bubbles, she said. That was our opening. They used to live in Lyon and now split their time between there and here. He is an opera singer and had been on tour for six months. They love French wine, come here often. I asked about their bottle of young Burgundy, which was on the by-the-glass list and which I’d wondered about before deciding to head toward Italy. They offered a taste, insisted, the man rising to get a glass from the bar and pouring me a couple of fingers. This is what wine does: it dissolves.

It was crunchy, bright. For me, a transition from Italy to France. And to Pinot Noir, the focus of my research, my paper, the conference that lay ahead this week.

I paid. I left. Walking into the bright late evening, I passed a woman seated on a stoop a few doors down. It was my server, talking into her phone, saying, Yeah, I’m already on break. Tonight there’s really nothing.