Wine Labels, Wine Ingredients

What, exactly, should be disclosed?

Last week, wine writer Talia Baiocchi published the views of four industry professionals on whether wine labels should list the ingredients used in winemaking. Although she classified the story as a “Hot Topic,” her interview subjects—a sommelier, a winemaker, a distributor, and a retailer—seemed rather circumspect, withal. The consensus was that ingredient labeling is possibly helpful and sometimes confusing, and that engaged customers will find some way to get this information, anyway. The upshot of the article: Why bother?

My own views on this subject are likewise colored by my work in the industry as a wine marketer, wine writer, and wine educator. But my views are also colored by my status as a wine consumer, and I think the consumer’s voice is an important addition to the mix.

I’m an avid back-label reader. I like knowing what has—and by extrapolation what has not—gone into the food I’m about to eat. I favor foods produced with minimal intervention and least processing, foods that are in their purest possible state, and, to the extent possible, expressive of where they’re grown. I avoid foods that are genetically modified, hormone-fed, antibiotic treated, inhumanely farmed, or that contain artificial ingredients, preservatives, and additives. I’d rather go without a food—particularly meat and dairy products—than support industrial farming practices, which are often unethical and ecologically damaging.

I appreciate the existence of a national organic standard (albeit one whose creation was weakened by the interests of big business), and the federal nutrition and ingredient labeling requirements, because together these offer some assurance about a producer’s claims. Note that no one’s saying that you can’t make Cheetos. They’re only saying that if you do make Cheetos, you have to tell everyone what they’re made from, so people can decide whether to eat them. Personally, I don’t.

Wine is no exception. I don’t want to drink Mega Purple or citric acid (because I’m intolerant of it) or other additives if I don’t have to. So as a consumer: Yes. I would like to see more ingredient labeling on wine bottles.

Speaking as a marketer, though, I understand the complexities of this choice. First, I know that many consumers don’t share this level of interest in how their wine came to be. Some may care more that a wine taste the same from one vintage to the next, and so may be more willing to accept additives or other interventions in order to achieve such consistency. That’s not truly an argument against ingredient lists, though, because these folks could ignore the lists if they chose—assuming they actually understand what all that stuff is.

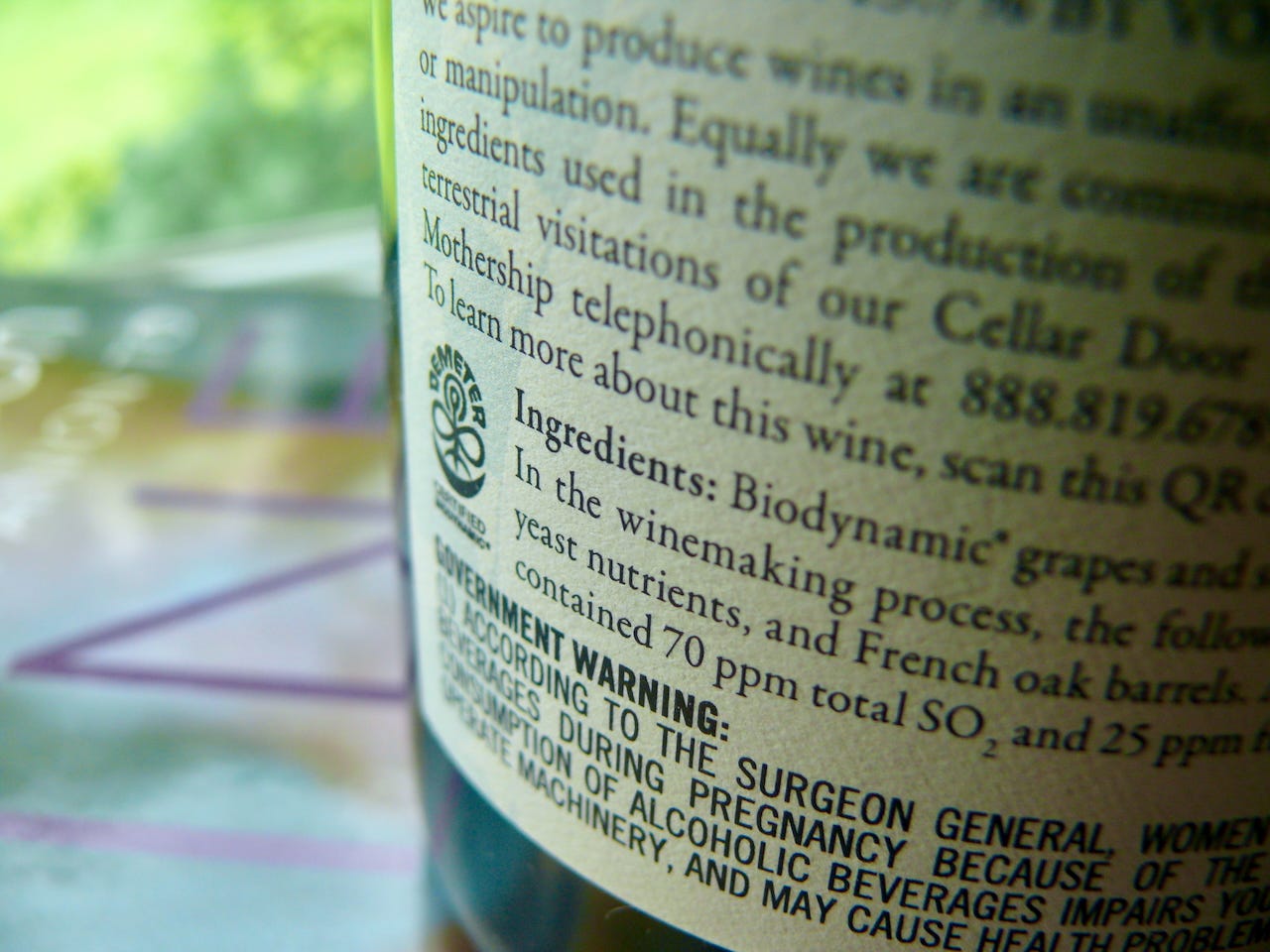

Relatedly, wine labels listing bentonite, isinglass, polyvinylpolypyrrolidone, and similar compounds do run risk of unnerving the public, or at least leading it somewhat astray. I saw this first hand when I worked in consumer sales at Bonny Doon Vineyard, a winery dedicated to ingredient and process disclosure. (The wine label pictured above is from their 2009 Syrah “Chequera,” farmed Biodynamically.)

On one occasion, we sent to media samples of a red whose label stated that un-toasted oak chips were used in the winemaking process. In his review, a writer remarked that the wine tasted too oaky to him, and that he’d wished we’d skipped the oak chips. These, though, had been used only to stabilize the anthocyanin during fermentation; they were in contact with the must for a short time, and did not add to the flavor profile of the finished wine. Moreover, the wine hadn’t spent much time in barrel during élevage, so I wondered whether the reviewer had mis-ascribed the grippy tannins of a young wine to something he’d read on the label. In this case, the oak chips disclosure was a ruby-red herring.

But that simply points to the need for more and better education, plus open communication between winemakers, media, and customers. Transparency is an important corporate tenet no matter what the industry, and consumer goodwill eventually accrues to companies that commit to it, even if initially the terms are vexing and hard to learn. Education and media coverage has, for example, led to a public that now grasps the nutritional difference between a natural oil that’s solid at room temperature and a purposely hydrogenated oil that may contain undesirable trans fats. If engaged consumers can learn that distinction, they can certainly learn that bentonite is a harmless fining agent, most of which precipitates out of the wine anyway.

Which brings us to another argument about ingredient disclosure, viz., What, exactly, should be disclosed? Grapes for sure, but what about wild yeast, or cultivated yeast? What about nutrients, acid, sugar, sulfur dioxide? What about the dry ice packed around the grapes on that sultry harvest afternoon? What about those Bonny Doon oak chips?

The key, absent federal labeling requirements, is simply to use good judgment. Disclose whatever seems important according to your winemaking principles and to your customers. For example, while it may be true that many compounds are detectible in only trace amounts in the finished wine, I do believe most vegetarians and vegans would want to know if casein (from milk), isinglass (from fish), or albumin (from egg) were used in the winemaking process. These are all fairly common fining agents, yet many vegans are unaware that animal products are often used in winemaking. “Isn’t wine just grapes?” they ask. Well, no, it’s not. A sensitive producer will stay tuned to the information needs of their consumer, and disclose accordingly.

So speaking as both consumer and industry professional, I do believe that ultimately, disclosure will lead to a better-informed market, and that this could in turn lead to more consumers choosing wines that are less manipulated, with fewer additives. This would be a good thing. Granted, that’s my value system, not everyone’s, but given the alternative, I prefer to put my faith in the success of a thoughtfully crafted, non-mass-produced, and possibly more expressive wine.

Eric Asimov, wine critic at the New York Times, recommended this article in the paper’s “What We’re Reading” column.