A Trip to the Rhône

As newlyweds, we spent four days in the Rhône to taste wines from its storied slopes

During our honeymoon, in 2002, my husband Steve and I spent four days in the Northern Rhône. We’d had a week in Paris—identified during the planning stages as Most Romantic Honeymoon Destination Possible—a week spent eating, walking, sightseeing, eating, sleeping, and eating. It was early June, and the weather was dulcet. We hit the all the tourist spots: the Tour Eiffel, the Louvre, Sainte-Chapelle, Berthillon—but also let ourselves stumble onto the extraordinary: a Sunday afternoon tango gathering on the banks of the Seine, a tiny chocolate shop where the chocolatier came out in lab coat to share his day’s creations. We dined in bistros, forgoing fancier restaurants, and picnicked in our hotel’s tiny garden on cheeses, bread, wine, and pastries. Did I mention the food?

Paris is wonderful, but we both love Rhône wines with an ardent passion, so had planned to finish our time abroad with a short tasting trip. We figured a long weekend in the Northern Rhône would give us a chance to taste from the major producers—Chapoutier, Jaboulet Aîné, Guigal—and from a few of the smaller ones, too. This would serve as a kind of a reconnaissance, a chance to test, and sample, the waters, and to get a sense of what tasting wine in France is like.

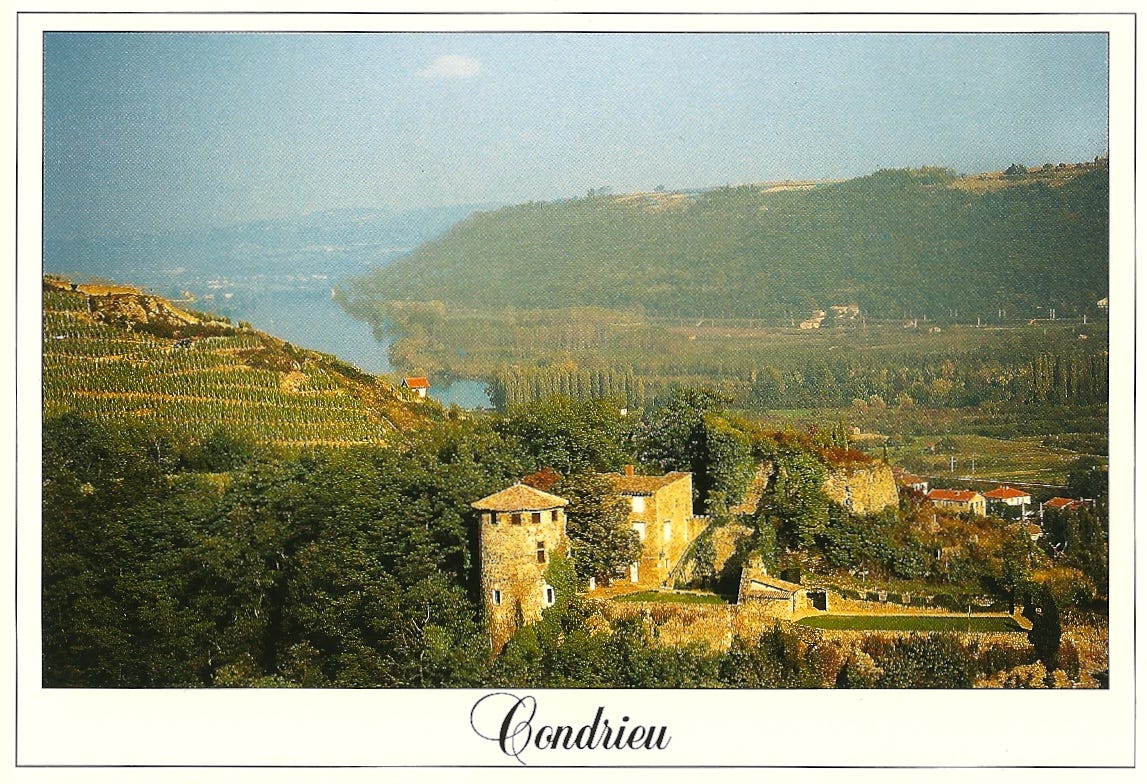

So we hopped a TGV to Vienne, rented a little Fiat, and sped down river to Condrieu, pulling into town on a Thursday afternoon. We checked into a tiny hotel, La Réclusière, then raced to Guigal to join a tour that was scheduled for the top of the hour.

My French is unstable at best—“Pardonnez-moi while I make steak-haché out of your beautiful langue”—so when we arrived breathless and fifteen minutes late at Guigal, I struggled to explain to the puzzled, very non-Anglophonic front desk attendant that we’d made prior arrangements. She and I were reaching a pique of exasperation when an elegant young man in an impeccable suit swept from the back office.

“How may I help you?” he asked, throwing me a lifeline with flawless English. This was, of course, Philippe Guigal, son of famed winemaker Marcel and an enologist in his own right, a partner in the enterprise.

He escorted us to the tour group, already deep inside the winery, and left us with a gracious smile. The guide, a slender young woman with flashing dark eyes, was making elaborate angular gestures with her arms as she effused over the fermentation room’s appointments. After five minutes, Steve abandoned any effort to understand her, while I persisted and wound up catching about every seventh word, which, as often as not, was “donc.”

That night we dined in Ampuis on salade nicoise and roast chicken, ordering Condrieu and Côte-Rôtie by the glass, then falling into bed to sleep like newborn kings.

Friday, day two. We rose early, breakfasting in the hotel’s bright dining room, slathering our bread with confiture and Beurre Échiré, the sweet, creamy French butter so beautifully cultured it’s lightly reminiscent of brie. After breakfast we folded ourselves once again into our tiny car and headed downriver to Tain-L’Hermitage, a small town ringed by a gravelly collar of steeply sloped vineyards. This is the heart of the diminutive Hermitage appellation, 321 acres of Syrah clinging to dizzyingly pitched terrain. The hillside is divided into myriad climats, each dominated by a different soil—granite, limestone, or clay—each subtly influencing the temperament of the resulting wine.

Our target in Tain was the Chapoutier tasting room, but we weren’t in a rush. In the outskirts of town we took a twisting side road, rising steeply into the plantings, parking at last behind one of the giant hillside signs, visible for a mile, that declare each winery’s holdings.

We stepped out of the car to take it in. The weather was gray and rainy, the broad Rhône twisting in the mist below us like a giant blue serpent. The red spring poppies were in full bloom, their bright papery petals beaded with rain, scattering like drops of blood along the road’s loose margin.

Sang des Cailloux—“blood from stones.” We’d had a wine by this name from Vacqueras, in the Southern Rhône—actually, we’d had a lot of it; it was our house wine for a year or so, before the dollar plummeted and French wine prices shot skyward. The label sported a spare, elegant engraving of the vineyard, with lumpy soil footing all the vines. “Cailloux” is French for pebbles, and even after pulling open Jancis Robinson’s Oxford Companion to Wine to read the article stones and rocks, we assumed the soil was simply, well—stony, studded with small pebbles, much like our New England till.

“These aren’t stones, they’re rocks,” I said, crouching down. They were the size of my fist, the size of grapefruits, some as big as soccer balls. There was no discernable soil in between. “How can the vines even survive?”

I should know better. I’m an experienced gardener, but since I am a terrestrial being, I sometimes forget that much, if not most, of a plant is deep underground, out of sight. This is where the veins of the plant meet the veins of the earth, and it’s where a lot of the magic happens, where water and minerals and microbes work an artful chemistry that fires the system and keeps it running. The roots are the plant’s engine room, thrumming and pulsing and driving their steam heat upstairs to fruit and seed, leaf and shoot.

We gardeners like it fertile. We’re trying to coax the maximum production in a short annual growing cycle, so we throw a lot of nutrients at the soil, then beg the plant to shoot the moon, because we only have one chance before frost flies in.

Viticulturists have other priorities. They’re raising perennials. Each season brings a new crop, a new cycle of flower, fruit, seed, and harvest, and each harvest is different. But the eye must remain fixed always on a sustainable alchemy, a stable marriage of vine to soil. Harvest will happen this fall, and the next, but these vines will likely outlive the vintner. They’re in it for the long haul.

In the vineyard, leaner soil is usually better. It keeps the canopy from overwhelming the vine, and keeps the fruit concentrated. It makes the roots tap deep in search of water, creating a network that buffers the plant against the vagaries of weather. And a thick mulch of stones offers good drainage while limiting evaporation.

Here in Tain, the Rhône takes a sharp east bend from its southerly route, so the vineyards above town tip nearly due south, amplifying the sun’s impact. The stones readily conduct and re-radiate heat, mitigating temperature swings between day and night. The steep slopes bake all day—Côte-Rôtie translates literally to “roasted slopes”—and this retained heat helps ripens the fruit.

Descending finally from the vineyards into the village, we found Chapoutier’s tasting room, parked, and pushed open the door. It was dim but welcoming, with a long bar along one side and climate-controlled storage along the other. A few chairs and tables had been placed casually about, and in the center of the room a portion of floor had been cut away and topped with sturdy glass to create a modest exhibit space. Below the glass were compartments filled with stones, each type separately identified. Clearly we weren’t the first visitors to marvel at the rocky terrain. Perhaps the good people of Chapoutier had grown weary of answering for their bony soil.

We were relieved when the host behind the bar returned our awkward greeting with English, handing us a long list of the winery’s offerings, perhaps fifty in all. “Which ones are open, now?” Steve asked the man, “Which ones may we taste?”

“Any of them,” the man replied. “You may taste anything you wish.”

A revelation. We’d been to tasting rooms in the States where perhaps as many as a dozen wines might be on offer, but rarely the full library. Still, as visitors painfully aware of our tourist status, we erred on the side of restraint, selecting only three reds and a dessert wine, all from the 1999 vintage.

We started with a Crozes Hermitage “Les Meysonniers.” Despite its sumptuous nose, this was thin on the palate and a bit disappointing. The Côte-Rôtie “Les Bécasses,” meanwhile, was young and quite tannic, but beautifully layered and full of promise. A Hermitage “Monier de la Sizeranne” offered an earthy, funky nose; here was a Syrah with a deep, meaty core. Finally, the dessert wine, a Muscat de Baumes de Venise, was like drinking a beautiful flower, with a honeyed nose and unctuous full blossoms in the mouth.

We didn’t buy any wine at Chapoutier. It was good but not spectacular, and it's possible it wouldn’t show as well here as it did in situ. There is an ineffable affinity between a wine and its place, and when one takes a sip of wine with a breath of the air that once washed its vines, there is an exquisite harmony, not replicable elsewhere; an experience of terroir. But really, what were we thinking? I’d bet the Côte-Rôtie and Hermitage would be knockouts by now.

Leaving Chapoutier, we headed south out of town to visit Jaboulet Aîné, a producer famous for the Hermitage “La Chappelle,” named after the picturesque stone chapel high in the vineyards overlooking Tain. The winery’s production, though, ranges up and down the Rhône appellations, from Crozes-Hermitage and Condrieu in the north to Gigondas, Vacqueras, and Tavel in the south.

We pulled into the parking lot, grateful for the enormous sign above the entry, since the cement stucco building looked more like a shopping mall or middle school than a winery. Inside, too, the modern office spaces were teaming with young professionals in business attire; it seemed we could have been in any industrial building anywhere in France, so generic were the surroundings.

The staff was a bit surprised by our unannounced arrival, but one young man gamely took us into his charge and led us around. We finished the tour in a tasting room that was rather more laboratory than lounge, appointed with sleek white benches and rows of sterile glassware. Our guide poured us tastes, amiably chatting about the wines and spitting expertly into a long steel sink, delighted at the opportunity to practice our language, and indulgent in our efforts to practice his.

We bought a bottle of the Côte-Rôtie “Les Jumelles” and headed back to our hotel, amused at the wholly different experiences at Chapoutier and Jaboulet. Still, we’d tasted some wonderful wines, an experience made all the more wonderful by being in the heart of the appellation, with fresh images of the vineyards dancing behind our eyes. Blood from stones, indeed.

After our whirlwind tour of Tain, we decided to stay close to home that evening, dining in the tiny restaurant in our hotel. We chose the five-course tasting menu, awkwardly translated into English on a little card the hostess offered, smiling. We managed to ascertain that there would be soup, something with calamari, something with pork, a cheese course, dessert, and a lot of wine. What we didn’t know was that the chef would continually provision us with tiny amusements between the advertised courses, lavishing us with his hospitality. The hostess whisked away our menu cards and headed for the kitchen.

The first wine arrived, a Verzier Condrieu, 1999. It was floral and fruity from the start, but after warming a bit it suddenly burst forth from the glass, a true apricot bomb. I’d never before tasted Condrieu, a white made exclusively from Viognier. The hit of fruit and flowers was powerful, perhaps too much so, but it helped me see why this grape is also used in small quantities in Côte Rôtie, the floral notes of the Viognier working to complement the earthy, meaty Syrah. Along with this the hostess served a tray of tiny appetizers, each no more than an amuse-bouche.

Then came a cold soup of fresh peas puréed with cream, topped with crème frâiche and a thin layer of aspic, a tiny tender parsley leaf decorating the center of the glistening gelée. My spoon slid easily through the layers, and as each spoonful entered the warmth of my mouth, the aspic vanished instantly, leaving behind the grassy green peas and cream, a taste of ephemeral spring.

Before we’d finished our soup, the second wine arrived, a Finon Condrieu 1999. This was closed at first and far too cold, but after about ten minutes began to give off the scent of lavender and a slight, vegetal astringency that married beautifully with the peas.

The hostess cleared our bowls and brought an entremet. Then another cold course arrived, a ragoût with chunks of meat in a thick base of tomatoes and onions. This was served on a bed of tender lettuces and garnished with tiny fresh and pickled vegetables—cauliflower and carrots, bean sprouts, borage flowers, fennel. The meat was tender and silken, but—what was it, exactly? Our minds now relaxed, we could recall only vaguely something about squid, and something about cheeks. We decided this dish must be squid cheeks—did squid have cheeks?—and that squid cheeks were good.

Now we were nominally only two courses into the meal, but were on our fourth beautiful little serving and well into our second wine. We were starting to unwind, to feel the cool, spreading effects of the meal reaching down to our core and out to the ends of our limbs. We had forgotten nearly everything we’d read on the menu, forgotten the sequence and name of each dish, forgotten to anticipate one course and the next. We were joined only to the present, and at the hostess’s mercy. We ate, we put down our fork, our spoon; we drank, we set down our glass. And we awaited her next tender ministration.

More wine now—this one a Bonnefont Côte-Rôtie 1999, a meaty offering from the slopes of the Rhône. And at last, the main course. Here was succulent meat, sharp and salty but meltingly tender, braised with new carrots, plump pole beans, and black olives. We sopped the earthy, rustic stew with hard-crusted peasant rolls studded with walnuts and spread with more of that beautiful Beurre Échiré. And we laughed at ourselves, now, realizing our error. These were, indeed, the menu’s “cheeks”—not squid but, naturellement, pork.

A cheese course followed. The hostess offered us a choice, and Steve selected a soft local goat cheese, Rigotte de Condrieu, which arrived drizzled with fruity olive oil and topped with fresh cracked pepper. I ordered a fresh, very soft goat cheese whose name I missed, but which was served in a small, shallow dish surrounded by a moat of cream and sugar. Tangy, velvety, and a little sweet, it was almost, but not quite, a dessert.

That was still to come. Steve had a crème brulée, cracking through the caramel to reveal a cool, smooth, nearly coffee-colored custard. It was delicious, with a haunting but completely unidentifiable flavor that, we learned from the hostess, came from a wine reduction. My dessert was something like rice pudding, but served with prunes stewed in wine and garnished with rosemary.

We could not have eaten one bite more, and we climbed the stairs to our bed a flight above, dazed and happy after a long day’s harvest.

Saturday morning, the bells of the town’s tiny church chiming through the mist in the distant square. Today was our day for serious tasting. Armed with a tattered copy of Parker’s “Wines of the Northern Rhône” that we’d found in a Parisian bookshop, we started making calls. Or rather, I started making calls, since, despite Steve’s pre-nuptial Pimsleur language course brush-up, he’d experienced substantial lingual paralysis on this trip and I wanted to save him from fresh horrors. Still, the combination of cold-calling and the Rhônish patois exacerbated my plight as I struggled to ask after tasting room hours.

Worse, though, was the dawning realization that we were perhaps out of luck. “I am sorry, Madame, we are closed on Saturdays,” answered one. “No, Madame, we are not open le weekend,” replied another. “We will re-open again next Wednesday.”

We had made a very American assumption—formed by our trips to California wine country, where the tasting room lights are always burning—that the producers would cater to consumer timetables and consumer need. If customers had the weekend off and wanted to browse around and taste, the wineries would naturally accommodate, n’est pas? Perhaps à Paris, ma chère Madame, or even down in Tain, but ici—non.

At last, success. I had phoned a tiny producer outside of Ampuis, Domaine Henri Gallet. The pleasant Madame Gallet replied that yes, they could be open today for tours and tasting, as she was expecting another small group to arrive soon. Could we possibly come at eleven? She patiently provided me directions, enunciating each word as if I were a child or deaf or both. I caught mention of a left turn at a pharmacy in Ampuis that I’d noticed on the way through, and beyond that lay only a few kilometers of rural road. She assured me there would be clear signage, and I hadn’t the heart to make her repeat herself more than once. So, clutching my sketchy directions, we hopped into the Fiat once more.

By some miracle we found our way, arriving at a spare farmhouse with a small sign by the door declaring the premises ouvert. We knocked, and Madame Gallet, waving us in, showed us and two French couples straight to the cellar. There she treated us to a brief discussion of the wines, and of their recent experiments with new oak. Finally, she offered us a barrel tasting of the recent vintages.

Here was a wholly new experience. Neither Steve nor I had ever tasted a wine in process, its work still underway. It was—not good, but interesting: full of tannins and fruit, all bumps and loud shouts, gangly but full of promise. How do you say that in French? What we lacked in language we made up for in enthusiastic pantomime, trying to convey to our host our appreciation for, if not the wine, at least the experience of tasting it.

Back upstairs in the modest tasting room, we sampled a few of the recent vintages. Monsieur Gallet joined us then, greeting the newcomers with sturdy handshakes. He poured us tastes from six bottlings of Côte-Rôtie, from the 2000 and 2001 vintages. They were remarkably different, some tannic and flat, others with a nose like pipe tobacco but lush to bursting on the palate. We purchased one from the second bottling of the 2000, a particularly rampant offering we thought would age beautifully.

While the Gallets were chatting with the French couples, Steve and I sipped and looked around at the bottles and trinkets arrayed casually on the shelves lining the walls. On one shelf I noticed a slightly curled Polaroid of a man, clearly taken while he was standing in front of said shelf. I held it up so Steve could see, and we nodded to each other knowingly.

Madame Gallet, noticing us suddenly, broke from her conversation to inform us, “C’est un critique Americain.”

“Oui,” we replied, nodding, we knew. It was Robert Parker.

They must have known he was famous—otherwise they wouldn’t have bothered with the Polaroid—but their attitude toward him was vigorously nonchalant. Madame Gallet couldn’t even recall his name off the top of her head, and seemed a bit surprised when we could. Here, Mr. Parker was, it seemed, simply another critic who landed on the doorstep every few years for a taste. Meanwhile, the Gallets would go on making wine the way they pleased, regardless of the appraisals of certain “critiques Americains.”

And so it was throughout the Rhône. Our hosts in this wine country had been supremely genial and welcoming, patient with our inadequate language skills, tolerant of our acute cultural ignorance, indulgent when it was possible to be so, regretful when it was not. That we were willing and earnest—and probably overly apologetic—might have helped our cause. But it also strikes me that when a region’s character is so grounded in place, so rooted and self-sure, it might be easier to stretch to accommodate visitors, to let them have a little piece of the solid thing you hold, because there’s plenty here to share. And it might likewise be easier to regard critique as simply irrelevant, because what we have will last, and will outlive the visitor. We’re in it for the long haul.

Our first reconnaissance trip to the Northern Rhône was over seven years ago, now. We’ve never returned—or should I say, we haven’t yet returned. Meanwhile, the 2000 Gallet Côte-Rôtie rests in our cellar, maturing. Perhaps we’ll open it on our tenth anniversary—it should be in its prime by then—to remember the trip when our own young marriage was gangly and new, and ready to age for a long, long time.

This story was originally published in January 2010 on Palate Press. It is reprinted with permission. Howard G. Goldberg, of the New York Times, generously recommended it to his readers.